Big gods came after the rise of civilisations, not before, finds study using huge historical database - Post from The Conversation website

Big gods came after the rise of civilisations, not before, finds study using huge historical database

When you think of religion, you probably think of a god who rewards the good and punishes the wicked. But the idea of morally concerned gods is by no means universal. Social scientists have long known that small-scale traditional societies – the kind missionaries used to dismiss as “pagan” – envisaged a spirit world that cared little about the morality of human behaviour. Their concern was less about whether humans behaved nicely towards one another and more about whether they carried out their obligations to the spirits and displayed suitable deference to them.

Nevertheless, the world religions we know today, and their myriad variants, either demand belief in all-seeing punitive deities or at least postulate some kind of broader mechanism – such as karma – for rewarding the virtuous and punishing the wicked. In recent years, researchers have debated how and why these moralising religions came into being.

Now, thanks to our massive new database of world history, known as Seshat (named after the Egyptian goddess of record keeping), we’re starting to get some answers.

Eye in the sky

One popular theory has argued that moralising gods were necessary for the rise of large-scale societies. Small societies, so the argument goes, were like fish bowls. It was almost impossible to engage in antisocial behaviour without being caught and punished – whether by acts of collective violence, retaliation or long-term reputational damage and risk of ostracism. But as societies grew larger and interactions between relative strangers became more commonplace, would-be transgressors could hope to evade detection under the cloak of anonymity. For cooperation to be possible under such conditions, some system of surveillance was required.

What better than to come up with a supernatural “eye in the sky” – a god who can see inside people’s minds and issue punishments and rewards accordingly. Believing in such a god might make people think twice about stealing or reneging on deals, even in relatively anonymous interactions. Maybe it would also increase trust among traders. If you believe that I believe in an omniscient moralising deity, you might be more likely to do business with me, than somebody whose religiosity is unknown to you. Simply wearing insignia such as body markings or jewellery alluding to belief in such a god might have helped ambitious people prosper and garner popularity as society grew larger and more complex.

Nevertheless, early efforts to investigate the link between religion and morality provided mixed results. And while supernatural punishment appears to have preceded the rise of chiefdoms among Pacific Island peoples, in Eurasia studies suggested that social complexity emerged first and moralising gods followed. These regional studies, however, were limited in scope and used quite crude measures of both moralising religion and of social complexity.

Sifting through history

Seshat is changing all that. Efforts to build the database began nearly a decade ago, attracting contributions from more than 100 scholars at a cost of millions of pounds. The database uses a sample of the world’s historical societies, going back in a continuous time series up to 10,000 years before the present, to analyse hundreds of variables relating to social complexity, religion, warfare, agriculture and other features of human culture and society that vary over time and space. Now that the database is finally ready for analysis, we are poised to test a long list of theories about global history.

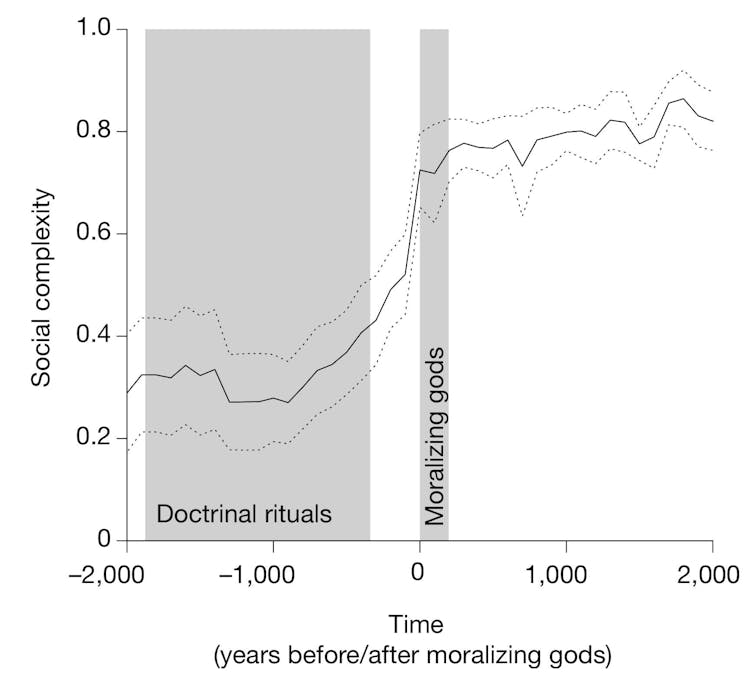

One of the earliest questions we’re testing is whether morally concerned deities drove the rise of complex societies. We analysed data on 414 societies from 30 world regions, using 51 measures of social complexity and four measures of supernatural enforcement of moral norms to get to the bottom of the matter. New research we’ve just published in the journal Nature reveals that moralising gods come later than many people thought, well after the sharpest rises in social complexity in world history. In other words, gods who care about whether we are good or bad did not drive the initial rise of civilisations – but came later.

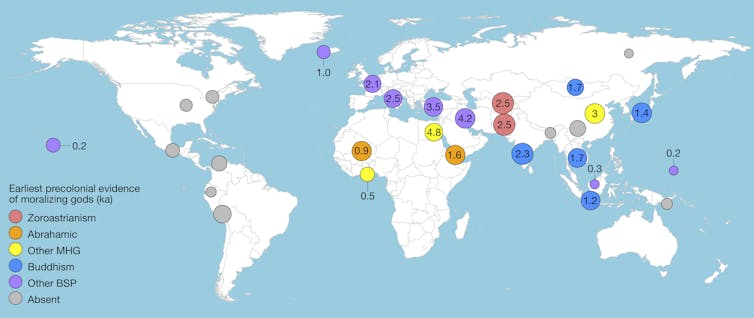

As part of our research we created a map of where big gods appeared around the world. In the map below, the size of the circle represents the size of the society: bigger circles represent larger and more complex societies. The numbers in the circle represent the number of thousand years ago we find the first evidence of belief in moralising gods. For example, Emperor Ashoka adopted Buddhism 2,300 years ago after he had already established a large and complex South Asian empire known as the Mauryan Empire.

Our statistical analysis showed that beliefs in supernatural punishment tend to appear only when societies make the transition from simple to complex, around the time when the overall population exceed about a million individuals.

We are now looking to other factors that may have driven the rise of the first large civilisation. For example, Seshat data suggests that daily or weekly collective rituals – the equivalent of today’s Sunday services or Friday prayers – appear early in the rise of social complexity and we’re looking further at their impact.

If the original function of moralising gods in world history was to hold together fragile, ethnically diverse coalitions, what might declining belief in such deities mean for the future of societies today? Could modern secularisation, for example, contribute to the unravelling of efforts to cooperate regionally – such as the European Union? If beliefs in big gods decline, what will that mean for cooperation across ethnic groups in the face of migration, warfare, or the spread of xenophobia? Can the functions of moralising gods simply be replaced by other forms of surveillance?

Even if Seshat cannot provide easy answers to all these questions, it could provide a more reliable way of estimating the probabilities of different futures.![]()

Harvey Whitehouse, Chair professor, University of Oxford; Patrick E. Savage, Associate Professor in Environment and Information Studies, Keio University; Peter Turchin, Professor of Anthropology, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and Mathematics, University of Connecticut, and Pieter Francois, Associate Professor in Cultural Evolution, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Skip to main content

Skip to main content

Comments

Post a Comment

Please let me know about the quality of content